Frank Underwood, Comcast and the FCC

If you haven't watched the second season of "House of Cards" (or, gasp, any of the show), be glad that Netflix just paid Comcast a lot of money to ensure that will be able to continue to do so in high-definition and 4K.

For those who are uninitiated, "House of Cards" is a show produced and distributed by Netflix; it is a take on a British show of the same name (1990). Our American version features Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright as Frank and Claire Underwood, two conniving, and deceitful Washingtonians and their ultimate quest for vengeance, power and glory stemming from those who betrayed Frank in the first episode (more about the show can be read here and watched here).

This isn't a post about the show, but more chatter about the overall way that we are (globally) consuming content (in all forms) and how providers, creators and consumers are all intertwined (for good, and for evil).

With the recent news that Comcast plans to purchase Time Warner Cable, as well as the net neutrality controversy in which Netflix agreed to pay Comcast for better bandwidth for content delivery to Comcast subscribers, I believe that the dam is beginning to crack, indicating a sea change in content delivery protocols, methods and laws for delivery across all channels and platforms.

Some might welcome this change as a necessary evil for the overall increase in quality, speed and content that the public seems to clamor for (especially in 4K). Others will most definately see this as an affront to net neutrality and an overreach by a (despised?) major corporation that has begun to acquire content providers such as NBC.

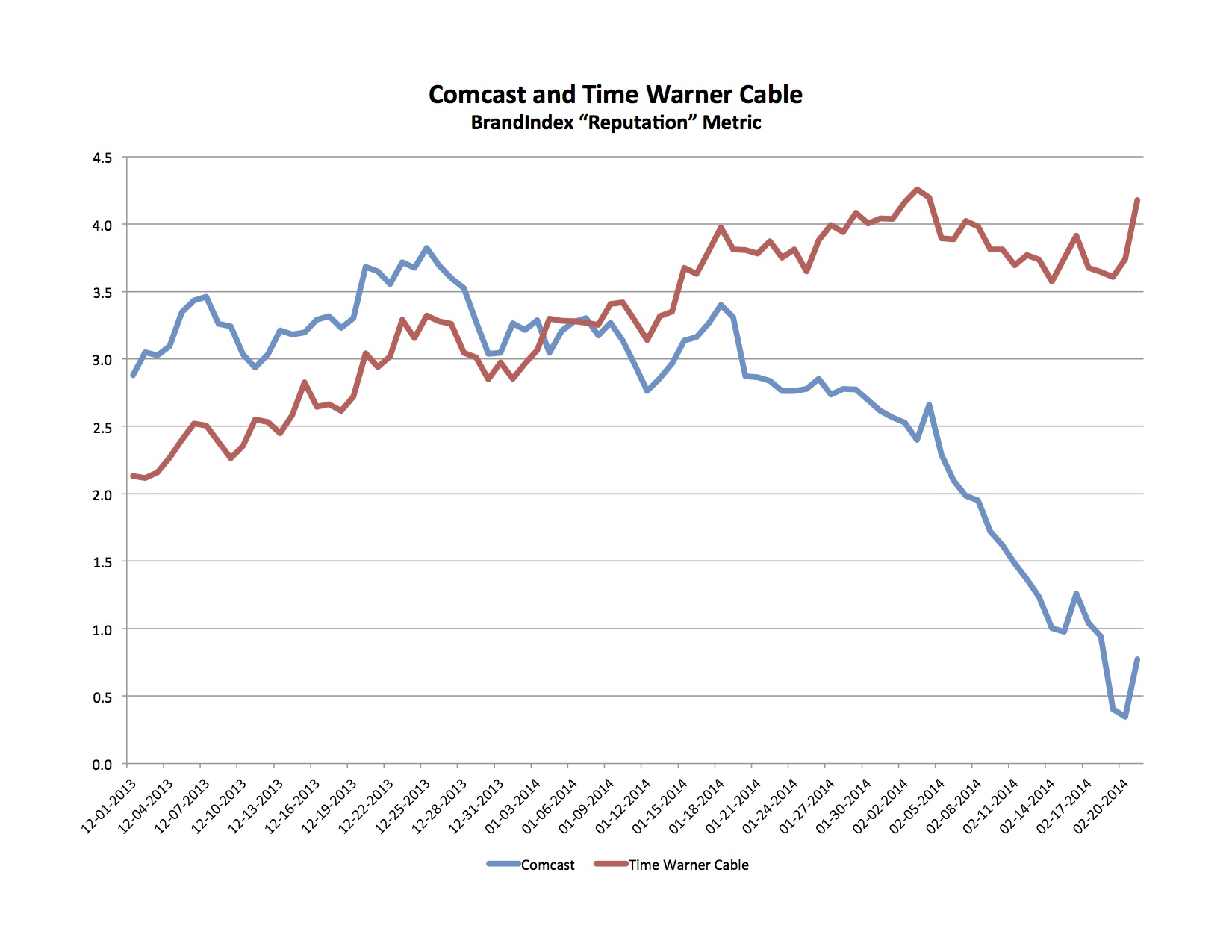

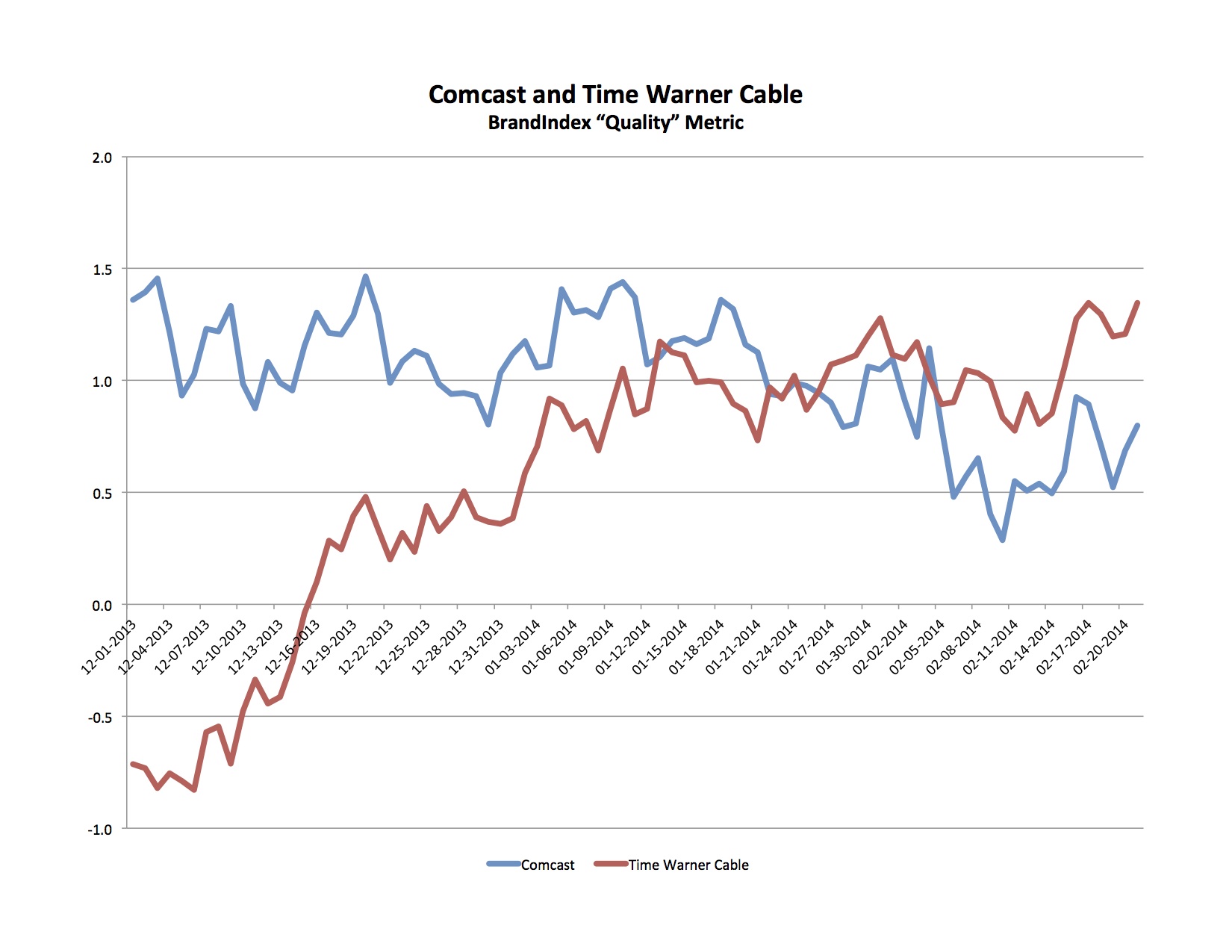

This, however, is a sweetheart deal for Time Warner Cable who has struggled for years to be seen as a company that provides consistent, high-quality service to its subscribers (which it doesn't). Recent polling conducted by BrandIndex (a subsidiary of YouGov) shows some interesting things.

As one would expect, Comcast's "reputation" and "satisfaction" metric falls sharply, but in an interesting turn, Time Warner Cable's metrics sharply increase.

So the acquisition is good for Time Warner, but has the opposite effect on Comcast. But it doesn't matter since, as Gigaom mentions, it's all about the broadband and its associated revenue stream:

According to UBS estimates, the combined company could see its consumer data-only revenues go from $17 billion at end of 2013 to about $23 billion by end of 2018. Voice revenues go from about $6 billion at the end of 2013 to $6.6 billion at end of 2018.

Really. Who cares if I am a happy subscriber -- just make sure I continue to pay.

Netflix had to pay Comcast in order to protect high-quality streaming - there was no other way to ensure that the content, for whom Netflix has begun designing around the viewer, makes it into the home.

It is critical that Netflix's content be delivered: it retains customers and makes the comany money. Netflix is starting to see that it has reached the innovators, early adopters and early majority and is starting to flatten in growth (or at least it is attempting to think about the very near future when that happens). It is a public company and needs to ensure that it's cash flow remains robust and that it can grow its market capitalization and attract investors. in order to do that it needs to innovate; House of Cards was just that innovation it needed as a proof of concept. Since the first season aired in 2013 (and was announced in 2012), Amazon has also gotten into the content creation service releasing Alpha House, Betas and, a whole slew of new shows in 2014.

So what does "House of Cards" tell us about what is actually going on in the content creation and content distribution industry? Well, unlike today's ability to binge-watch a season or two of a show, I guess you will just have to tune in later and find out.